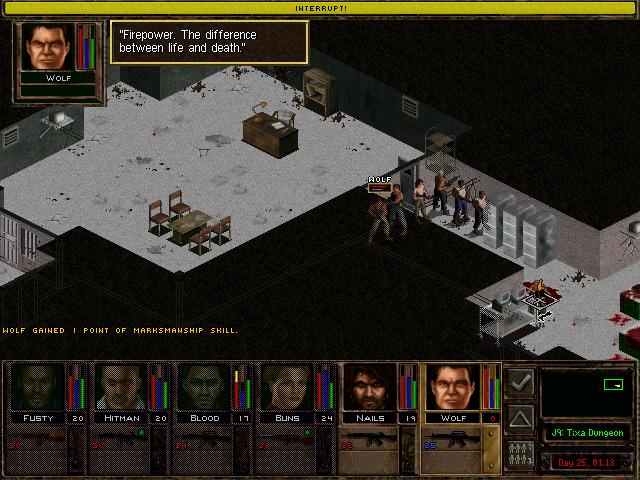

He weaves together marketing materials, technical documents, and interviews with engineers, managers, politicians, and money men. But Latour takes these dry topics and tells a mesmerizing tale blending ethnographic adventure, philosophical manifesto, and hard-boiled detective fiction. It’s a story that should be boring, consisting of government appropriations, Gantt charts, hardware failsafes, scope changes, and variable-reluctance motors. In his 1996 book Aramis, or the Love of Technology, sociologist and philosopher Bruno Latour tells the story of Aramis, a real, futuristic French public transit system that had massive financial backing in the 1970s but never got past the prototype phase. We need more of that in video-game writing, and I tried to do that in my most recent book, J agged Alliance 2, by learning from one of my favorite pieces of writing. Popular books about movies acknowledge the materiality of the medium and the many forces that combine to shepherd a film project from conception to completion. And if you grab a popular book about a movie off a shelf, it might contain film criticism, but it's just as likely to delve into how the movie got funded, what the production process was like, and the lives of the people who made it. They’re similar to movies in that respect. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, but it’s worth recognizing that video games are often team projects that involve technical, artistic, financial, and managerial coordination.

Most popular writing about video games tends to be experiential, focusing on the relationship of the player to the game.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)